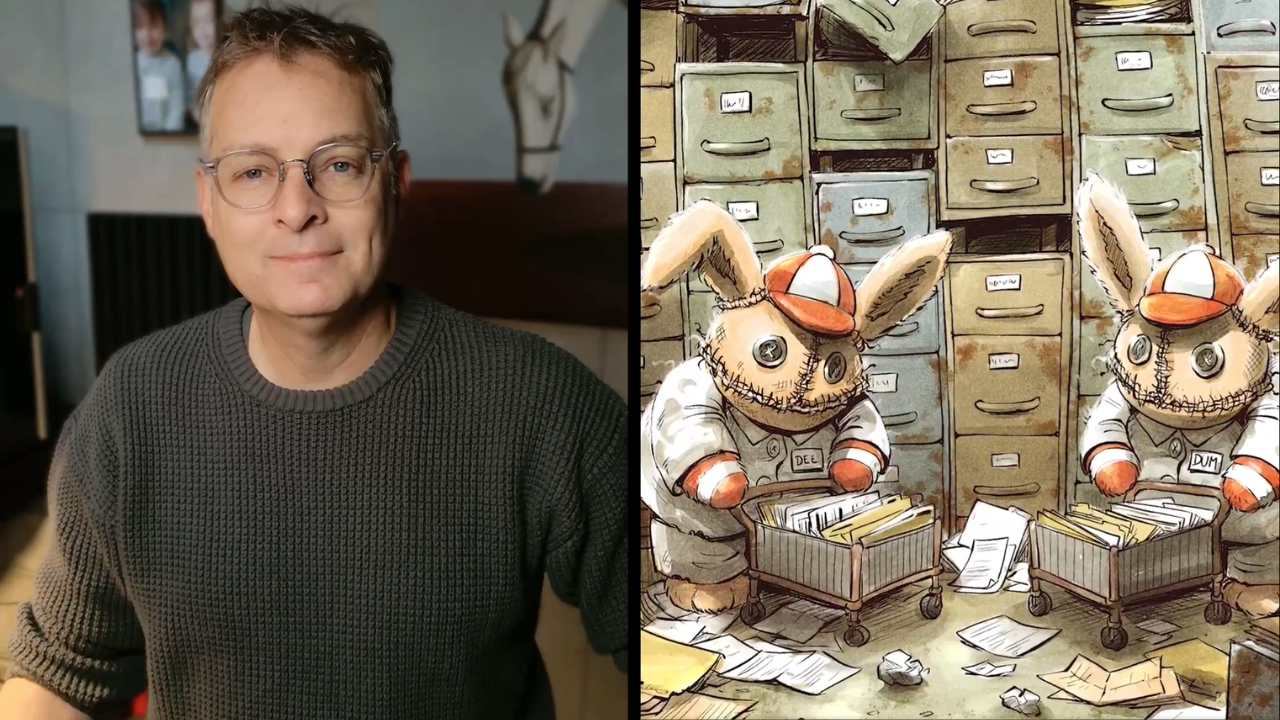

Sagi Schliesser is the CEO and Founder of CrazyLabs, a globally renowned mobile games publisher and studio specializing in hyper-casual, casual, and hybrid-casual games.

CrazyLabs consistently ranks among the top mobile game publishers worldwide, with over 7 billion downloads and a portfolio featuring some of the most popular titles in the industry.

Under Schliesser’s leadership, CrazyLabs has established a strong global presence with development hubs and partnerships across key gaming markets.

The video version of the interview is available on Mobidictum’s brand-new YouTube channel.

How did you start your career

I started my career in a small startup doing B2B. That was a really long time ago. However, two big parts of my career have been spent in InsurTech. I spent 14 years in InsurTech, handling huge projects, such as B2B, working for years to sell and then years to implement.

I worked for and helped develop one of the biggest products for property and casualty insurance in Europe. And then, I spent almost 15 years in gaming. These are completely different industries with different types of sales.

I told myself I didn’t want to do any more B2B and long cycles. I wanted to work with users, consumers, and I wanted to know much faster if something works or doesn’t work. So gaming, for me, was the answer.

What year did you decide to stop doing B2B and move to the consumer side?

Actually, it was phased. I decided around 2008 or 2009. Then, it took almost two years to make the switch in parallel. The interesting story is that I created a company called TabTale back then. We started as TabTale while I was continuing as the GM, CTO, and VP of R&D for Sapiens, a Nasdaq-traded insurance company.

It was a very complex and tiring journey, trying to do both for two years. Then I realized my passion was with consumers, and I made the leap to working 100% on TabTale, now CrazyLabs.

Why gaming? You could’ve chosen anything consumer-related.

In my eyes, and this is personal to me, gaming is the best business in the world. You deal with all aspects of consumers—their psyche, who they are, why they come to your game, and what experience you want to provide them. Delivering that experience involves psychology, gameplay, art, music, animation—everything.

It’s a mix of technical analytics because everything is data-driven and creative, which goes beyond data. I’m a right-brain and left-brain person, and this combination of data and creativity was what I was looking for in my career.

In university, I studied psychology, computer science, statistics, human behavior, and UI. For me, gaming is the best business that combines all of these elements.

How did you come up with the name TabTale?

Creating names for startups is harder than you can imagine. In the beginning, all names sound great and stupid at the same time. Only time can prove if they’re good.

We thought about many names, and most were bad—I don’t even remember them. Someone on the team suggested “Tales and Tablets” since our early focus was on stories and tablets. That became “TabTale.”

CrazyLabs has been in the industry for almost 15 years. That’s a big achievement. Running the studio for so long, up to 300 people globally, with hubs in Istanbul and other locations—can you share some pivotal moments?

I’m not someone who stops easily. When we hit a wall, I ask, “Where’s the window?” If the window is closed, I look for the roof. I’m an optimist and believe you learn from failing.

We’ve had many challenges and successes that didn’t turn out as expected. Our industry is so dynamic. Users have changed a lot since 2009 when we started. They were first-generation users of smartphones and app stores. Now they’re pros, and that has completely changed how they interact with games.

Regulations, infrastructure, and app stores have also changed much faster than other industries I know. If you’re not ready to adapt, you’ll struggle.

I speak to our employees every three months in sessions, and I visit every site quarterly or twice a year. I tell them we are not a company for people who want a lot of stability. People who work with us long-term understand this because we constantly evolve.

We’ve had a lot of failed experiments—tablets, VR, AR, and more. But in our industry, you fail much more than you succeed. That’s the nature of the business. You have to fail a lot to succeed that every success is golden.

Image Credit: CrazyLabs Instagram

What are the difficulties of running this studio as a founder? Was there a co-founder at some point? How was that situation?

So, I created CrazyLabs, but I’ve also been part of other startups and made investments in startups. For my personal journey, I think founding power is really important. The energy, power, and resilience that a founder brings are critical.

It’s a bit like what parents bring to a family. They are relentless—they need to succeed. Even when they get hit, they keep going because, for them, there’s almost no choice.

In startups, you do have a choice, but you still need to be relentless.

I’ve done it with more than one venture, but it’s like real life—you hear about stories of divorces, and we also had a “founder divorce.” Misalignment of interests can happen. By the way, it’s harder when you start succeeding than when you fail. When you fail, it tests your resilience, but breakups are more common when success comes.

Success can make you think you’re smarter or more special than others. You lose some humility, and this can lead to conflicts. Breakups often happen because everyone thinks their contribution is the key to success.

It depends on who you co-found with, how long you’ve known them, and how aligned you are. I know many friends who stopped being friends after founding companies together. It’s a huge challenge.

I believe it’s better to have multiple founders because sharing responsibilities is priceless. Of course, the downside is you share the equity, but having someone take on some of the responsibility is invaluable. It’s really hard to be a founder alone.

I’m lucky to have a co-founder now who’s not only a great partner but also a friend. He’s smarter and better than me in many ways, which is what you want in a co-founder. That makes my job easier—I just do the talking!

It’s interesting how success can bring ego into play and break partnerships. People may feel they worked harder or deserve more credit.

It’s not always about who worked harder. For example, when three partners start a company, they all immediately become important: one is the CEO, one is the CTO, and one is the CMO. They’re all “C-level” executives, even if before they were just students. But as the company grows and success comes, egos emerge.

One person might start to question why another is the CEO or why they aren’t in charge. In a small startup, hierarchy means nothing because decisions are made together. But when you have 30 or more employees, you can’t make decisions as a group—it becomes chaos. Someone needs to take responsibility and make the final call.

I’ve spoken to many founders who faced this challenge. It’s not something people share openly on LinkedIn, but it’s common for co-founders to come to a point where they say, “I want to be the CEO now that we’re successful.” This often causes breakups.

Today, there’s more awareness of these issues. Organizational psychologists and advisors are helping startups and founders communicate better. It’s like a marriage—you need constant communication. When communication stops, you drift apart.

When was your first big success or “hit”?

We created TabTale in 2010-2011, and while we had some early success, it wasn’t easy. Raising money back then was hard because investors in our region didn’t believe we could sell directly to consumers, especially in markets like the U.S. or the UK, which were culturally different.

Investors advised us to focus on building platforms because that’s what we’re known for—technology, not consumer products. While their advice made sense, I didn’t want to go back to selling B2B. I wanted to connect directly with users and test if I could deliver value to them.

We raised a small amount of money and even sold my apartment to fund the company. In 2011, our focus on books and educational apps gained some traction, but monetization wasn’t great. We raised around $1 million total, including personal funds, and brought in some angel investors.

However, by the end of the year, we had spent most of it without seeing great results. We tried pivoting—creating greeting cards and other ideas—but nothing felt right. It became clear that raising more funds with the conditions we were offered wouldn’t be sustainable.

In 2012, we decided to become profitable and scale the business. One of my co-founders went to his wife after this decision and shared the plan. They laughed about it for an entire weekend. But in startups, as in any business, there’s a strange reality—you need to set aggressive targets even if they feel unrealistic at the time.

In an established business, you aim to grow 5–10%, and that feels reasonable because it aligns with market growth. But in a zero-to-one process, like a startup, you need to believe in something bigger. You set ambitious goals, declare, “This is where we’re heading,” and then go for it. Sometimes, you fail spectacularly. However, I’ve found that setting aggressive targets often creates “magic moments” where you actually meet or even exceed them.

In 2012, after losing everything and almost having to shut down the company, we set a goal to become profitable. We focused heavily on monetization and better understanding our users. For instance, we analyzed user behavior and noticed they weren’t completing long gameplays or books—they’d only get through about two-thirds of the content. So, we shortened everything and added additional monetization options.

By the end of 2012, our revenue grew tenfold, and we broke even. In 2013, we scaled even further, growing revenue by seven times and becoming highly profitable. By the end of 2013, we became the number-one publisher for kids on the App Store. It was the first time we hit number one in any category.

At that point, we had tens of millions of downloads and significant success, both financially and in terms of user engagement. People were playing our games and downloading them en masse. It felt incredible.

I’ve read somewhere that many Israeli founders aim for an early exit to secure financial stability and then, in their second venture, aim for billion-dollar companies. But you sold your apartment to fund the business instead of taking those offers. Why didn’t you sell back then?

For founders, the decision to sell often depends on personal circumstances and priorities. When I was younger, in my late 20s, before I had kids and a family, I was more willing to take risks and explore different ideas. But when I started TabTale, I was approaching 40. At that stage of life, I felt this was the startup where I wanted things to go exactly as I envisioned them.

When you’re younger, you think, “If this one doesn’t work, I’ll move on to the next one.” But for me, this was the venture where I wanted to do things right and make decisions based on my own standards. I didn’t want to sell technology to other companies—I wanted to reach users directly.

The offers we received at the time didn’t align with my vision. I decided it was better to push through, even if we failed. I didn’t want to look back and feel like I’d settled for “almost.”

I’ve always been someone who goes all out, knowing I’ll face many failures before success. But when success comes, I want it to be significant. In our case, it worked out really well.

If you could go back to day one of TabTale, what advice would you give yourself?

I’d say, “Be careful with the co-founders and the first three or four employees—they are critical, almost like co-founders themselves.” Also, find a really good mentor—not someone who’s in it for money, but someone who knows the business and genuinely wants to help because they’ve been in your shoes.

A great mentor can be priceless. The advice and guidance they offer can help you avoid mistakes, scale the business, and move faster. While I had some good advisors early on, I didn’t have enough. With more mentorship, I could have made fewer mistakes and progressed more quickly.

Do you think you can still have a mentor at this stage?

I think I’ve moved beyond needing a traditional mentor. Instead, I have strong partnerships and people I can consult with. I also have a great co-founder who complements me perfectly. We spend a lot of time together—working, talking, even playing—and we’re not afraid to challenge each other.

At this stage, it’s about having meaningful conversations about the business and exploring different scenarios. While every individual has a bit of ego, between us, it’s about what’s best for the business. I feel incredibly lucky to have a partner like that.

We’ve also learned a lot from our industry peers, like Voodoo, SayGames, and Easybrain. These companies, even as competitors, have shared valuable insights during events or conversations. At this stage, it’s not so much about learning basic principles but about leveraging relationships and partnerships to navigate the challenges of scaling and evolving.

The Israeli tech scene is great—there are so many tech startups. But you mentioned that back when you started, consumer-focused startups weren’t as common. Now you have mobile gaming giants like yourself, but back then, as an early adopter of the consumer-focused model, did you have any entrepreneurs you looked up to in the scene or worldwide?

I remember when we started, I tried desperately to reach Rovio, the creator of Angry Birds. At the time, Angry Birds was amazing, a massive success. I tried to connect with them but didn’t manage to.

At events, you’d see companies like Ketchapp, which made a big impact and later got sold. Then Voodoo emerged, doing incredible work and essentially building an industry that no one really understood how to penetrate at first. They paved the way for many others.

In our industry, there have been great leaders who showed us the way. My biggest role model, someone I admire deeply, is Ilkka from Supercell. I met him recently at an event. The way Supercell operates and builds teams is amazing. It’s very admirable.

There are many people I look up to—not just in gaming but in tech as well. Some are local, from Israel. Often, I try to see who is doing better than us, analyze their methods, and figure out what I can learn from them. There’s always something to learn. I’ve learned a lot from our competitors and partners. It’s an ongoing journey of evolving and improving.

If gaming hadn’t worked out, what would you have done instead?

I think it would still have been consumer-related. I’m very interested in the combination of mental health and technology.

For example, CrazyLabs is an investor in a company called Kai. They create apps that supplement therapy, helping people and enhancing the therapy process. If it weren’t for gaming, I think I might have pursued something like that earlier. When they pitched their idea to me, I felt, “Wow, if I didn’t already have my company, I would’ve joined their ride.”

I love the combination of psychology, human needs, and tech—using technology to help people. That’s the kind of venture I would have pursued if I hadn’t gone into gaming.

When did you decide to change the company name and branding, and how did you come up with the new name?

That’s an interesting story. After our major success in 2012, we continued growing in 2013 and 2014. Everything looked great. We analyzed our progress and thought we were in a golden era. Parents were upgrading their devices every couple of years, and their old devices were being passed down to kids. As we were focused on kids’ games, this trend meant more customers for us.

We were the number-one publisher for kids’ games, and we thought, “This is it—we’ll keep climbing.”

But then, two things happened around 2015 that we didn’t anticipate.

First, regulation. Web regulations started coming to mobile, and we should’ve seen it coming, but we didn’t anticipate the scope. The app stores tightened rules around monetization and ads to avoid complaints from parents.

Second is the generational shift. By 2015, the kids who had gotten their first devices in 2012 or 2013 were no longer as impressed by mobile games. They had already played on their parents’ phones and were moving on to different kinds of games. The clear segmentation of “kids’ games” started to dissolve.

We saw a shift—kids were playing the same games their parents played. The market for kids’ games shrank, leaving us with a much smaller audience. We had to decide what to do next.

We considered selling the company but ultimately decided to reinvent ourselves. We identified two major segments: teenage girls and a strong culture of creating fast, casual games through prototyping.

This led us in two directions: casual simulation games for female audiences (like dress-up and fashion games) and fast-paced hyper-casual games. We had strong female teams passionate about creating fashion games, and we also had expertise in rapid game development.

At the time, hyper-casual wasn’t even called that—it was referred to as “super casual.” We began venturing into that space. However, we still had kids’ games in our portfolio, which created a brand dissonance. It was clear that we needed to make a change.

Initially, we created a sub-brand called CrazyLabs. We loved the name—it reflected our spirit as “positively crazy” people who try to break rules and reinvent things in a good way.

Eventually, we realized kids’ games were in our past, and CrazyLabs was our future. We transitioned the entire company to the CrazyLabs brand. It started as a sub-brand but grew to represent our main focus.

We even have a mascot called “Shrimpy.” It’s cute and reflects our playful nature.

How do you see the mobile gaming industry right now? What challenges do you think will be solved in the short term or long term?

I think the market is maturing. In business school, they teach you about maturing markets: it starts as a blue ocean, then turns redder and redder. That’s exactly what’s happening in our industry.

On one side, there’s been so much success that it’s brought in significantly more supply, but demand hasn’t grown at the same pace. Now, there are many more suppliers competing for roughly the same demand—or maybe slightly growing demand.

It became particularly evident post-COVID. While gaming still grows overall, the supply has skyrocketed. You see this in mobile gaming, console gaming, and even AAA titles. There’s now a surplus of high-quality games, but only so many hours people can spend playing and so much money they’re willing to spend.

For example, games like Candy Crush have proven to be “Evergreen.” Many thought games like this would last five to seven years, but they’ve lasted much longer. They’ve built such a deep ecosystem—better marketing, better campaigns, constant updates—that they stay relevant for years.

Meanwhile, new games find it much harder to break into the market. A game has to truly stand out with something fresh and innovative to attract players. And even then, the competition is fierce.

You also see it with social casino games. For example, Jelly Button introduced raid systems, which was an innovation in the genre. Then, Moon Active built on those ideas. But after that, many others came in and replicated the concept, making the space even more crowded.

This cycle repeats. Someone finds an innovation, and the rest of the market rushes in. Right now, for example, you’re seeing hybrid monetization and hybrid casual games take off. But even this space is becoming saturated.

In hyper-casual, the same thing happened. Initially, it was a blue ocean—very open. But now the market size has plateaued, and so many hyper-casual games already exist that the space has become incredibly competitive. Many studios, including us, are pivoting to hybrid models or bigger, deeper games.

The challenge now is to find the right niche, whether in hybrid casual or other areas. You can’t just copy trends—you need to bring something new to the table, something that resonates with players.

For us, we see two key areas of opportunity:

- Hybrid Casual Games: These are games that combine hyper-casual gameplay with deeper monetization mechanics. It’s still evolving, and there’s no one-size-fits-all formula. But we’ve been working on hybrid casual games even before the term became popular, and we continue to invest heavily here.

- Female Simulation Games: We believe this is an untapped market with tremendous potential. Most of the gaming industry is male-dominated, and the types of games that cater to women—like fashion and decoration—are still underrepresented.

For example, we have had success with Super Stylist in the past. It did well with over 170–200 million downloads, but it was limited by technical debt since it was created in 2017. Now, we’re launching a new game called Glow, developed by an almost entirely female team passionate about fashion games.

Women make up a large segment of mobile gamers, and they spend more on these platforms. If we can create games that truly cater to their passions, we believe we can unlock enormous potential.

In a maturing market, where supply continues to grow, the key is to find your niche and excel in it. For us, hybrid casual and female simulation are our main focus areas.

When is Crazy Labs’ 15th anniversary?

It depends on where you start counting. We began working in a café in June 2010 but officially incorporated the company in December 2010.

I’m less focused on celebrating anniversaries, though. I’d rather celebrate major milestones, like launching a top-grossing game or reaching significant download numbers. Time is nice for measuring progress, but for me, it’s more about achieving concrete goals.

So, what’s coming up for Crazy Labs in the next few years?

Our main focus is on two fronts:

Hybrid Casual Games: We aim to strengthen our position as a top publisher and continue building a strong portfolio in hybrid casual games. We always strive to be number one, though being in the top three is still great. The competition is fierce, but that’s what makes it fun.

Female Simulation Games: We want to break into the top-grossing charts with these games, aiming to be a permanent presence there rather than just a fleeting success.

What’s your one piece of advice for someone starting a mobile gaming company today?

My advice is to understand the market dynamics deeply before jumping in.

Many people think having an idea is 90% of the work, but in gaming, the execution is everything. The quality bar is incredibly high. You need to get so many things right—game design, marketing, monetization. It’s not enough to just build a great game; you need to ensure it gets discovered and played.

The days of “If you build it, they will come” are long gone. Now, it’s “If you build it and spend a lot of money on marketing, maybe they’ll come.”

You need to understand the curve your game is going to follow—whether it’s a casual game, a hyper-casual game, or a hybrid game. Each has its own dynamics. Without understanding this, you’re essentially wandering in a desert without a map.

If you don’t know the market dynamics, spend time learning. Study the data, talk to people in the industry, and figure out what it takes to succeed. The more data-driven your approach, the better your chances.