Estonia is a treasure trove of small indie studios and developers releasing nuanced and interesting games. From Disco Elysium by ZA/UM, Death & Taxes by Placeholder Gameworks, Haiku the Robot by Mister Morris Games, and now the list of popular games with interesting concepts is filled by yet another Estonian developer, Mike Klubnika and his recently gone viral new game called Buckshot Roulette.

Mike never gave interviews before, so I am honored to say that this exclusive opportunity he agreed to sit down for is the first chance you will get to read about his approach to making games. Mike and I talked about a whole range of topics, including Buckshot Roulette, his earlier work, his approach to making games, and his attitude toward fans, and I even got a chance to ask why you couldn’t type GOD or DEALER as your names.

Hello Mike, thank you for coming to my interview. With so many eyes on you after the success of Buckshot Roulette, how does it feel? What is it like?

Well, I already had experience with people having millions of eyes on my games, pretty much since the beginning. In the horror space, it’s not uncommon for a lot of YouTubers to cover your games. So in one way, it feels exciting, especially when I have been making art since I was a little kid, and I was not that good at it. Also, because of that, nobody was really interested, so to see millions of people engaging with the content, leaving comments and all, it’s something that I am really grateful for and do not take for granted. But at the same time, it can be overwhelming because the more people engage and view your content, the more pressure you will have with future releases because people expect good content from you. Before I could make any idea that is fun and interesting to me, and release an unpolished mess. It would get 500 downloads, which isn’t a lot, but then there is also a lot of creative freedom when you just don’t have that many expectations from other people.

You mentioned you had a background in art. Tell me about where you came from artistically. What background did you come from into Gamedev?

My background is mainly 3d art. I obviously started out as drawing, but then the first software I made art in was Macromedia Flash 8 or something. But I was never good at 2d art. That’s when I found and started using Blender. So, I would go home after high school and not really play games or go to the gym; I would just learn how to do 3D art. This proved pretty useful because I was pretty proficient in designing art and had one less thing to learn when it came to using a game engine like Unity, for example.

I noticed that a few years ago, Jacksepticeye played your game, and you had a tweet about how you used to watch him a lot when you were twelve, and now he is playing your game.

Yeah, that was crazy. I remember waking up to that.

What do you think was the reason why The Other Side, the game Jacksepticeye streamed, skyrocketed so much? What do you think clicked with the audience?

I think when the game was released, firstly, the graphics were similar to Iron Lung, which was a pretty big horror game at the time. The game came out a year after Iron Lung, which is why I think it is relevant in that context, but more importantly, I think the game was really unique. There weren’t really other horror games that are like it. Mechanically, it’s very interesting.

Other than Iron Lung, what other things inspire your games? Not just The Other Side, but games you make in general.

One of the inspirations was definitely Iron Lung, but it was more subconscious. The main inspiration for my game’s settings is just overall gritty industrial environments, like bathrooms in Silent Hill and the overall asylum with rusty metal, which might be covered in blood, but you can’t really tell because it is so grungy. It’s a very interesting aesthetic. Also, when it comes to visual style, you can compare it to Iron Lung, but you can get away with not properly UV unwrapping objects and having the textures look weird and stretched in some places, and nobody is going to think like ‘Oh that texture is weird and stretched’ because it fits in with the aesthetic’s grunginess.

This reminds me of a design of a dealer in Buckshot Roulette. He feels like he stands out but fits in. How were you able to attain this unaesthetic aesthetic?

It is a lot easier to make a dirty and grungy scene than to make something clean and perfect. When I painted through all of the textures in Buckshot Roulette, I just added dirty and grimy leaks to every corner. And it just blends the entire thing together rather than having different objects.

Was that also your approach to creating the horror aesthetic? Because the horror aesthetic seems to be persistent in the entirety of your work.

Well, I guess most of the environments in my games are industrial. Brutalist architecture is a huge inspiration for my environments, and they add to the horror ambiance because the player never really feels like they can rest anywhere. Everything is designed to fit a specific purpose, and it does not think about the user experience. Like the machines in Buckshot Roulette, they serve a specific purpose: to cut the wire in the machine, and that’s everything. No matter where the player is, they can never feel comfortable or rest. Also, in The Other Side, everything you see in the room only exists to fulfill that specific task. There are no decorations to make you feel comfortable.

It’s interesting that you mentioned the idea of comfort because another question I wanted to ask was related to how a player cannot input two very specific names in Buckshot Roulette: GOD and DEALER. Was this by intention, and why?

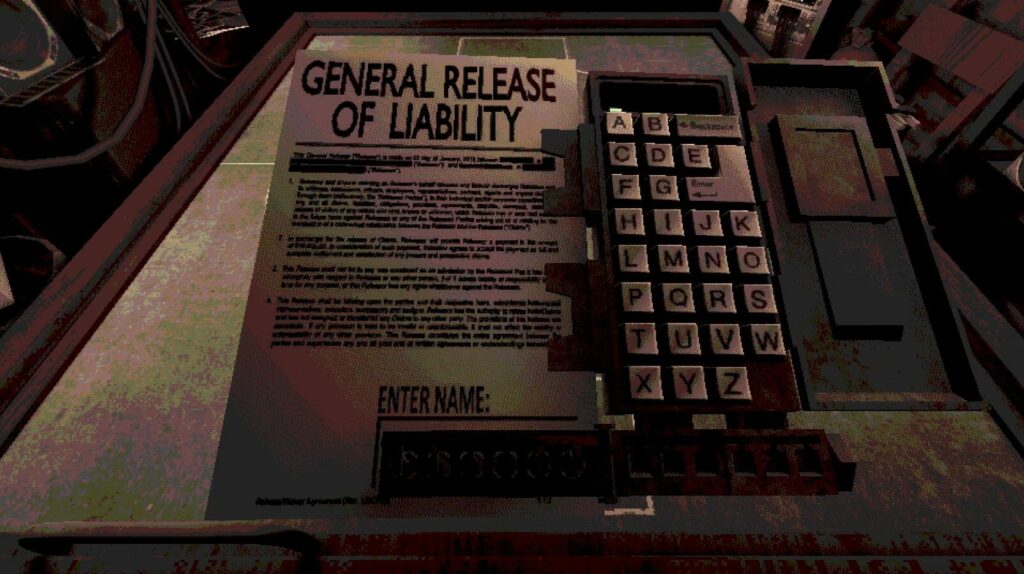

Ok, so the DEALER is because I was messing around with the machine, and I decided to name myself that. Then, I realized that it’s weird you can name yourself as the dealer. Shortly before release, I added the thing where, during the second round, where items are introduced, you could take a general release of liability that was signed by GOD out of the item box. It made sense that since GOD had already signed the game, the name was thus taken. A lot of people think this is deep lore, but the names are just taken already.

You can’t be someone who exists within the story, but video games and deep lore go hand in hand. What do you personally think about doing deep lore in your games? Would you be interested in it or aversed?

I like lore in video games, and the story is important, but what is funny about Buckshot Roulette is it has almost no lore. I set out to make a game of Russian Roulette with a shotgun, so there was no intended lore. Compared to the previous games, where there was plenty of it. And what is funny to me is that of all the games, the game I chose to put almost no lore into is now getting wiki pages and videos analyzing the lore, and so I feel like I should have added more lore.

Do you think that maybe in a classic horror fashion, he was, at some point, a dead child or killer of dead children?

I wish I could have answers to those questions, but I have no backstory for the dealer. It’s just the person who dictates the deal.

What I noticed as a player is that the dealer at no point tried to one-up me or pull a trick that he didn’t warn me about. And I associated a trait of straightforwardness with lore.

When it comes to the personality of the character, when you watch movies about casinos like Ocean’s 11, dealers are very professional and follow the rules of the game, and you expect them to act that way, so in that regard, I can see where the assumption comes from. I can see it as a personality trait.

Another thing I wanted to ask about Buckshot Roulette’s design is the consumables. Handcuffs, for example, have a very interesting animation when you give them to the dealer. Why does the dealer take them instead of you placing them on him directly? What was the intention?

I didn’t think too deeply about it because first, you have the dealer handcuffing you, but when it comes to the player handcuffing the dealer, which was the first logical assumption, and handcuffs were supposed to float around the table, the design perspective it made more sense that a dealer’s hand would come instead. It felt more grounded in that regard.

What was the purpose of introducing consumables in the first place?

Some of the items are very simple, like cigarettes, which give you health, but at the same time, the presentation of the player smoking the cigarette just adds to we’re at the top of the nightclub ambiance. In that regard, it just looks cool. But clearly, from a game design perspective, it just adds one health and the same goes for the handsaw, which makes the shotgun do two damage, but purely from a representation standpoint, it just makes a player feel like a badass because you take a saw, saw off the barrel, and now you have a sawed-off shotgun. Other items, like magnifying glasses and beer for example that, are something I thought would be interesting from a game design perspective because essentially, what you have in Buckshot Roulette, in comparison to a traditional Russian Roulette with a revolver, is a fixed sequence of shells that are inserted, and you have a lot of different mechanics that you do not have with a revolver. You can rack the shotgun now and see exactly what comes out of the hole. You can look at the round that’s currently inside, and it’s just interesting; you’re basically playing around with the sequence that is inside the shotgun. I think that added quite a bit of value to the game, so I am happy that I made the items.

As a player, I still struggle with understanding the logic of a beer consumable; when must I use it as a player?

The beer is weird. Others don’t understand it either because of the description. It’s something like, “You rack the shotgun, ends round on the last shell.” It’s confusing, but when you try it, you figure it out. But when it comes to the use of the item. In case it’s fifty-fifty, you can basically rack the gun, see what comes out, and you either increase or decrease the odds of firing a blank. Also, there is a weird gimmick in the game where, as soon as the shotgun is emptied, the player goes first. So if you have a table full of beer, and you’re not really feeling the round, you can drink all of the beer, empty the shotgun, and it would give you a new turn.

That is an interesting way to stack them that I haven’t thought of. With all the topics that we have already covered, how do you think the environments you put your players in and the rules of the game tell the story of the game?

All of the game rules, especially when it comes to the players choosing to shoot themselves. There had to be a fairer incentive for that, which is why one of the main rules of the game is that if you shoot yourself with a blank, you get to go again. That, I think, is very important, and without it, not many players would be shooting themselves. I have seen many playthroughs where people decide to shoot themselves; they know it’s a fifty-fifty or a sixty-forty chance, and you see them get anxious momentarily. That, I think, is the main rule that adds to storytelling because otherwise, it would be just you and the dealer shooting each other. It makes an entire game feel more risky.

And do you think a dealer would have benefited from the opportunity to shoot himself as well?

The dealer can shoot himself with a blank and will also get a new turn.

So it’s there?

Yes.

I am a little surprised; I thought only the player had that privilege. This does, however, make me curious about the dealer’s AI. Did you train it to take risks, too, and how? Because the dealer’s AI does appear very tactical. How did you train him in a way to makes him challenging?

The first thing I did when I began development of the game was I made a prototype in Tabletop Simulator. That was more or less what the game basically is. I played it with a few friends, and we also made a few design choices that we changed later. But I basically modeled the AI after what my friends did. It is relatively simple. I think it is five or six if statements and the way the dealer makes decisions is basically he will use the items, and those items will sometimes give him information like what is the current shell in the chamber. For example, when there is only one shell in the gun, you’re going to know what it is because all the other shells have been ejected, so you can deduct what the final shell is going to be. And in the case of magnifying glass, he is also going to know it. But for example, with the handsaw, let’s say the dealer doesn’t know what shell it is, he doesn’t have a magnifying glass, and it’s also not the last shell, which basically makes it a coin flip. If he has a handsaw in that scenario and decides to shoot the player, he will use the handsaw. In that way, AI is very simple.

It’s surprising, but it also makes sense. After hearing the origin story, I am even more curious about how you came up with these ideas.

The way I come up with ideas is sometimes they just come out of nowhere, and other times, when I’m brainstorming, it’s just like asking questions: “What if I do this with this?”. For example, I have a game called Concrete Tremor, where it’s like a game of battleships but with apartment buildings, and that was how it started: “What if we played battleships with apartment buildings?” And the same thing is for Buckshot Roulette. I got the idea a year ago because I found it interesting from a design perspective. Russian roulette with a shotgun actually seemed feasible, but at the time, I just couldn’t figure out a good design for it. So it’s really just about asking questions and seeing if it’s interesting.

What other industry projects inspire you to come up with game ideas?

When it comes to other industry projects, it’s mainly other indie developers, especially on itch.io. Specifically developers like Ken Forest and Adam Pipe, and also Ken Horwood. All these developers basically create short horror games. They are mechanically interesting and based in interesting environments, and they inspired me because they also showed that if you want to make a game that sticks with people, it doesn’t have to be something that is a six-hour experience. It can be as short as ten or fifteen minutes, and it can still be a memorable and fun experience, which was very inspiring to me.

Speaking of influences, ever since Buckshot Roulette released, I have some friends, who are outside of the gaming industry, and yet they spammed me with the soundtrack for your game. What are the principles by which you write music in order for it to accommodate the atmosphere and vibe of the game?

That’s cool! When it comes to Buckshot Roulette specifically, at first, the music was just a horror ambiance. You had scary sounds, but then I sort of came up with the idea that what if the game took place in a nightclub? I think it sort of makes the game and the tabletop turn-based experience more intimate because when you are inside the game room, all of the techno music is muffled, and it takes up all of the low frequencies and all of the high frequencies of the items and interactions are going to be more easily heard. And it just makes the experience more intimate. Also, when you kick down all of the doors, when you hear techno music, or when you smoke a cigarette, the goal is to make a player feel like a badass. To make them feel powerful.

But why did you include the shaking animation on the shotgun when the player is holding it? How does that contribute to the badass feeling?

Because there are moments where if you decide to shoot yourself and it’s, say, a 50/50 chance, it can still be nerve-wracking regardless of how many cigarettes you’ve smoked or how many doors you’ve kicked. It also felt intuitive that when there are loud bangs, alcohol, and nicotine involved, there is no way you are going to hold the gun steady.

You are somehow able to mix this badassery with genuine fear. There is something scary about Buckshot Roulette, yet the game is only aesthetically horrifying. Are you more interested in making games with a horror aesthetic, or are you interested in the future to incorporate more elements of horror in your games?

I have always been the type of person who does not find things like jumpscares very interesting. I think they can be very effective, but it’s just not what I’m after. The most memorable horror for me is conceptual horror, stuff that messes with the human mind. One of the main inspirations for my games is Arthur C. Clarke. He is a science fiction writer and made a bunch of horror stories that I read a few years ago and one of the scariest things that I have read from the books was one instance where there were some dudes printing nine billion names of God on the top of the mountain, that’s how the story is also called – Nine Billion Names of God. They print the names of God, and there’s all of this machinery and monks, and when they go home, they look at the night sky, and all of the stars just start flickering away. They shut down until it’s pure blackness. Imagining a scenario like that is something very scary, and I’ve always been interested in pursuing that type of horror, where there is no scary monster or loud noise, just a pure concept, a conversation in a correct context, or it can be even more effective with a traditional jumpscare, but it is also very difficult. I am more interested in horror aesthetics.

Do you think maybe that is why people started making wikis about Buckshot Roulette? Because in the absence of lore, they started to explain the concept to themselves.

Yeah, I guess that’s the big part of it. When they have not explained anything that comes to the environment and the goals, they start filling in the blanks. Basically subconsciously. Even when it comes to the nightclub, you can tell from the interior what the exterior looks like and other things in a similar fashion.

There is also a small scene where you walk to the dealership, and you see you’re on a pretty high floor, and there is a long way down. It also implies that it’s a huge brutalist techno music building.

Yeah, the derelict warehouse adds a lot because the place where the game takes place is in the top left corner of the nightclub; it’s away from all the people who are probably having a lot of fun, and you’re just there with this creepy dealer, and you can’t hear music that well either, it’s so muffled, and it makes you feel in one way or another lonely.

Was loneliness something you intended a player to feel, or was it a side effect you discovered later when designing the game?

When it comes to music being muffled, just from a sound design perspective, partly it was the goal because it separates the player from the rest of the people at the nightclub. Also, in the soundtrack for the game, the first song is very melancholic; it’s quite sad, and it does build the atmosphere of “yes, I am badass, but at the same time, I have nothing to lose.”

Related to the idea of having nothing to lose, Buckshot Roulette has multiple endings depending on multiple factors, and in one of them, you see the gates of Heaven as you are killed. Is the way those gates are depicted how you also see the pathway to the afterlife?

Well, personally, I don’t know what the afterlife is. The gates of heaven look like that because I wanted to shock the player with “This is where you are now; good luck”.

It was a funny detail, with the spikes poking out, which isn’t something you naturally expect. It’s heaven, as if it’s in the middle of Estonian winter.

I guess it could be that heaven looks like that because God played Buckshot Roulette and died, so it might be what is left of heaven now since he is no longer there. It could be a good way to look at it.

All interpretations are valid!

Yeah, exactly.

And there are a lot of conversations to be had on this. Do the intentions of the player or designer for the game’s lore matter more? Do you welcome player interpretations?

Generally, yeah. I am up for interpretation. In my games, there is lore, but it’s so detailed that the larger picture is more or less unexplained. I always welcome interpretations. I find them interesting to read, and I always go, “I wish I could tell them about my interpretations, but I don’t want them to conflict with theirs because I think they are just as valid as mine” when the game features such minimal lore especially.

To the people making the wikis and actively trying to dig for lore in Buckshot Roulette, is there anything specific you want to say to them?

No, I don’t think I have anything specific. I would say keep doing what you’re doing.

Maybe to someone, that’s enough. My last question to you would be, considering your viral popularity, there may be a lot of people interested in following in your footsteps and starting to make games on Itch.io, trying to come up with something. Some may want acknowledgment, some may want to do cool stuff. Is there any advice you, as a dev with experience, may have for those interested in following your footsteps?

My main advice would be to stay consistent. If you want to make games, then you just have to keep practicing and working on it. It’s like any other skill in that regard. Also, at first, it’s not going to be very successful. It’s important to keep putting stuff out there. Specifically, I would advise against making a huge project as the first game. It should be the simplest thing you can think of. With that very simple project, you will learn a huge amount.

You mentioned how many skills you had to master to put out games; it must be really difficult learning each one of those things on your own.

Yeah, I guess I would add that it is useful to look at game development not as a single thing but as art, sound design, coding, and music. You can take those step by step. I started off by making 3D art and just basic renders and texturing models to share on the internet. Then, I don’t think I mentioned this earlier, but before I got into Unity, I looked at what programming language it uses. It’s C#, and I actually took a small course on C#. It was a small course on Codecademy. It took like two weeks, and it’s very useful to look at those parts separately. You learn coding and 3D art, and you’re more experienced now to actually start using the engine. It might not be for everything. You can jump straight into the engine and pick those up as you go along. Depends on the person.

Thanks again for coming, Mike. It was a pleasure talking with you, and I hope you face all the challenges in your future projects in the same manner! This was a really fun conversation to have.

Thank you for having me. I have not been to interviews before, so it was a very interesting experience. I rarely get to talk to someone one-on-one about game dev.

And thank you to all who read this article and played Mike’s game. Game development is one of the most challenging forms of art, which takes a lot out of a person, so to see some many people play Mike’s game is truly heartfelt for Mike and the whole gamedev community. You can check out Buckshot Roulette on Itch.io. As of the publishing of this article, this game was also streamed by Markiplier. Even if Mike did not intend for this game to have any deep lore, this game proves to be a fascinating phenomenon on how fans create it, and it would be very interesting to observe how its history develops from here and on.

NEXT: Interview about Starfield with Ryan Janes, VP of Commercial in Fancensus